Courage

Making the Intangibles Tangible

How the Drucker Institute and S&P Dow Jones Indices are giving investors a chance to put their money into companies that manage effectively beyond just financial results

By T.A. Frank

An odd thing about the S&P/Drucker Institute Corporate Effectiveness Index—a vehicle that allows people to put money into those companies that are most in sync with Peter Drucker’s core management principles—is that no one set out to create it.

At least not at first.

The index is based on the Drucker Institute’s corporate rankings, which began to be developed in 2013 and which since 2017 have served as the foundation for The Wall Street Journal’s Management Top 250 list of “the best-run U.S. companies.”

The rankings show how some 750 major corporations stack up according to dozens of third-party indicators, which together measure a company’s overall “effectiveness”—defined, to use Peter Drucker’s words, as “doing the right things well.” The individual indicators reflect a set of tenets that Drucker laid out across five areas: customer satisfaction, employee engagement and development, innovation, social responsibility and financial strength.

By applying objective data to aspects of corporate performance that are often dismissed as too nebulous to measure—such as employee engagement and innovation—the Drucker Institute has made the intangibles tangible. All of this, meanwhile, has been done in furtherance of a social mission: to prompt top corporate executives to think about how to best serve the interests of all of their stakeholders, not just their shareholders.

It wasn’t until last year, however, that the Drucker Institute discovered the statistical model used for the rankings also had real money-making potential for investors themselves.

“It was like setting out to purify water, and then stumbling into having developed a new cola,” says Zach First, the Drucker Institute’s executive director.

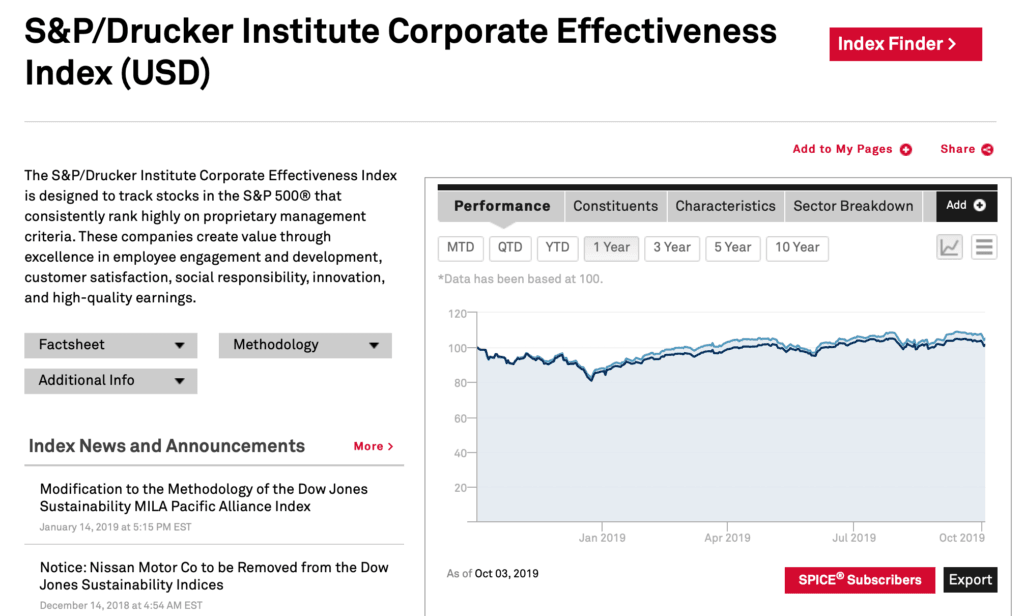

Over the five-year period that ended September 30, the S&P 500 offered investors a return of 10.84%. The S&P/Drucker Institute index would have offered a return of 13.26% over that same span. Over the past year, the S&P 500 was up 4.25% as of the end of September, compared with 7.88% for the S&P/Drucker Institute index.

In a market that plays a game of inches, that is a striking performance.

The result is that what began as an effort to help dislodge the mindset that corporations exist only for the sake of maximizing shareholder value has also yielded a compelling product for those who care a lot about shareholder value.

Of course, those attracted to this new financial index are likely to be investors looking for companies that excel at more than just elevating their share price. Embedded in the index is Peter Drucker’s view of what it means to be a truly “responsible” corporation.

Specifically, Drucker expressed that companies need, first and foremost, to satisfy their customers’ needs because “it is to supply the consumer that society entrusts wealth-producing resources to the business enterprise.” He also believed that a corporation must take care of its employees, maintaining that if “worker and work are mismanaged” it will, “by creating class hatred and class warfare, end by making it impossible for the enterprise to operate at all.” What’s more, Drucker wrote, companies must constantly pursue innovation so as to serve their function as society’s “specific organ of growth, expansion and change.” More broadly, Drucker asserted, management must “make whatever is genuinely in the public good become the enterprise’s own self-interest.” And, finally, Drucker held that none of this was in conflict with a company’s financial health. Management’s “first responsibility,” Drucker declared, “is to operate at a profit” so as to fulfill the role of business as “the wealth-creating and wealth-producing organ of our society.”

By the numbers

80%

The portion of a company’s total value today that typically lies in intangibles that aren’t captured on its balance sheet, a notable rise from about 20% in the mid-1970s, according to the Embankment Project for Inclusive Capitalism.

The initial push to see whether this holistic worldview would translate into a lucrative selection of stocks came from the Drucker Institute’s board. After all, they figured, if you could measure which companies were best-managed, couldn’t investors also use that information to make above-average returns on their portfolios?

Even Drucker thought that share price was a decent gauge of management’s effectiveness in the long run. “Despite its follies, foibles and fashions,” he said, “the stock market is a good deal more rational than the ‘experts,’ at least over any extended period of time.”

As simple as this was to suggest, however, putting into practice proved extraordinarily complicated. For starters, the Drucker Institute’s rankings are an assessment of the recent past. An investment is a bet on the future.

Even figuring out the basic composition of the index was tricky. How far down the list should you go? To the company that stood at No. 100 in the Drucker Institute’s rankings? To the company in 200th place? To 250, like the Journal does?

How much weight should you give each company in the index? Should they all be treated the same? Or do you favor particular stocks—and, if so, which ones?

What should you do about companies with lopsided numbers—for example, Facebook, which has shown outstanding strength in its financials yet also outstanding weakness in social responsibility and customer satisfaction?

It would take a lot of experimenting to figure this out, and it would also take sufficient faith in the concept to devote the time and funding to the work.

Beginning in the middle of 2017—and for most of the next year—the Drucker Institute was met with more setbacks than success. Number-crunching by several investment firms kept yielding the same finding: A financial product based on the Drucker Institute rankings was fine, but it just seemed to track the broader market. It appeared pretty ho-hum.

“There were some bad days, for sure,” First recalls. “But we had a moral conviction born out of trust and out of more than a decade of seeing Drucker’s core principles in action. So when we created an investment product that initially didn’t pan out, my belief was: That must be on us, the way we were approaching things. Drucker knew too much for us to give up on him then.”

What was needed, the team felt, was a partner with a deep understanding of the methodology and principles behind the rankings and with a willingness to look where others hadn’t.

The nudge out of gridlock wound up being a testament to the benefit of long friendships.

Rick Wartzman, First’s predecessor as executive director of the Drucker Institute (and, along with data scientist Larry Crosby, one of the original architects of the corporate rankings), was having a catch-up lunch in the summer of 2018 with a childhood pal, who had recently become head of an energy division of S&P Global. The firm’s flagship product, the S&P 500, is a market index of many of the top companies in the United States.

Wartzman mentioned the effort to create an investment product based on the Drucker rankings, and the friend sensed an exciting opportunity. Within a few days, he put Wartzman and First in touch with some of his S&P colleagues.

This soon led to a meeting in New York between First and Peter Roffman, who is head of innovation and strategy for S&P Dow Jones Indices.

As someone whose job is to look for unconventional products, Roffman was immediately intrigued.

Powerful Picks

The S&P/Drucker Institute Corporate Effectiveness Index has outperformed the S&P 500 over the last year, three years and five years.

“Right off the bat, I knew this checked some boxes,” he says. “The philosophy at work was in line with a growing interest in long-term corporate performance, and it encompassed factors like ESG”—environmental, social and governance measures—“while adding other dimensions such as employee engagement. We could combine business potential, doing the right thing and the name of Peter Drucker, a giant in business history.”

Roffman put Kelly Tang, S&P’s ESG analyst, to the task of looking into the idea more closely and carrying out due diligence. Tang flew out to the West Coast to pay a visit to the Drucker Institute at Claremont Graduate University. Coming from a giant corporation, she couldn’t help but wonder what kind of ragtag outfit she might find at a campus-based social enterprise with a staff of just 10.

“I was told by some of the people in my group, ‘Let us know if they even have an office,’” Tang remembers, with a laugh.

The skepticism didn’t last long. The more detail that Tang and others at S&P soaked up, the more impressed they become. “We read up on the principles and the methodology and academic underpinnings of the rankings,” says Tang, who quickly reported that the Drucker Institute would make a credible partner for S&P.

The next step was to see whether the Drucker Institute rankings could form the basis of a useful index and, in turn, a promising avenue for investment.

That’s much easier said than done. Relatively few indexes are able to surpass the S&P 500 in their returns over the long haul.

Tang started to run some tests, based in part on a set of historical Drucker Institute corporate rankings going back to 2012. The results guided her choices.

For instance, she elected to confine her selection to those companies that were already in the S&P 500 and to replace the Drucker Institute’s financial strength score with an assessment of financial quality that S&P has used in other products for the past five years. All of the other metrics—for customer satisfaction, employee engagement and development, innovation and social responsibility—would stay the same as in the Drucker Institute’s corporate rankings.

Then Tang made what may have been the most consequential decision of all: to eliminate those companies that were notably inconsistent in their scores across the five categories. There was a temptation to Winsorize—a term for ignoring any individual scores that were statistical outliers—but this, she felt, would negate what made the Drucker rankings unique.

“You couldn’t just be good at one thing,” says Tang, who has done other research into the value of long-term thinking among corporations. “The company had to be strong in multiple areas.” This led to the exclusion of titans like Facebook and Amazon, which has scored off the charts in terms of innovation but has lagged in social responsibility.

That, though, created its own dilemmas. Amazon has seen its stock outperform the S&P 500 by several hundred percent, and many equity analysts are bullish about its future. But Tang insisted on staying true to Drucker’s principles. “I thought of the ideals being pursued,” she says.

First notes that a prudent investor has additional reasons to prefer companies without glaring highs and lows. “Amazon has clearly bet that innovation is the one thing that’s going to drive its business, and it might be right,” he says. “The Drucker view, though, is that on balance you want to go with the company that’s consistent across multiple dimensions, because if for some reason its weaker scores become a source of risk, it’s nowhere near as well set up to manage that as a company that’s strong across the board, like Apple or Procter & Gamble.”

“We could combine business potential, doing the right thing and the name of Peter Drucker, a giant in business history.”

In the end, Tang came up with an index that selected the 100 top performers under the new criteria. She then weighted them according to their overall effectiveness score instead of by their market capitalization, which would have been a more conventional tack. “Selecting score weighting requires the power of your convictions and an utmost belief in the process underlying the Drucker ranking system,” Tang explains.

The formula also had the benefit of being simple and transparent. And one more big plus: It appeared to be a solid investment product. When Tang ran the numbers backwards over six years, the Drucker-based index outperformed the S&P 500 by about 200 basis points.

Last February, some six months after S&P Dow Jones Indices team and the Drucker Institute began collaborating, the S&P/Drucker Institute Corporate Effectiveness Index was launched. The two organizations are now working together to make the index available to retail and institutional investors.

“We’re hoping for adoption on a number of levels: getting people licensing it, approaching it, referring to it,” Roffman says. “It will also advance the goal of the Drucker Institute to promulgate its values.”

The timing could be fortuitous. In August, the Business Roundtable issued a statement signed by 181 CEOs that the purpose of a corporation should be to benefit all of its stakeholders: customers, employees, suppliers, communities and shareholders—exactly the kind of comprehensive perspective that the Drucker Institute has been urging. The proclamation supplanted one that had put shareholders first.

“After a long interlude, the business world is slowly returning to Drucker’s insight that a concern with balancing the interests of all stakeholders is integral to effective management,” First says. “And we think that over the long term it’s also integral to effective investment. Part of our mission here is to change how investors think about investing.”

In the meantime, the Drucker Institute has landed a great new asset of its own: Kelly Tang.

A few months ago, with data scientist Larry Crosby ready to move into emeritus status, Tang joined the Drucker Institute as its senior director of research. “What made me jump was the mission-driven and values-focused nature of what the Drucker Institute is trying to do, without judging or pontificating,” she says.

Tang is now preparing the corporate effectiveness rankings for 2019.

Monday Mandate

What will you do on Monday that’s different?

Consider All Your Stakeholders

Make a list of all your organization’s stakeholders, give yourself an honest grade on how well you’re serving each of them and discuss ways you could improve.

Build on Success

Like the Drucker Institute did by using its corporate rankings to create a financial index, consider what product or service is working well—and then imagine how you might innovate by building a new product or service off of it.

Invest Your Values

Analyze your investments—both in your personal portfolio and, if you’re able, your organization’s—and adjust them, need be, to better align with your values.