Peter Drucker’s favorite way to make management’s abstractions tangible was to analogize society and its organizations to the human body. In a pandemic, this laces his writing with a bitter irony.

“A healthy business, a healthy university, a healthy hospital cannot exist in a sick society,” Drucker wrote in 1974. “Management has a self-interest in a healthy society, even though the cause of society’s sickness is none of management’s making.”

Society is literally sick from the novel coronavirus that has infected millions and killed hundreds of thousands around the world. But it is also metaphorically sick insofar as management has let atrophy the very strengths we need to effectively navigate this crisis.

Over the past 40 years, according to the Academic-Industry Research Network, large publicly traded U.S. corporations have cut from 50% to just 6% the share of their profits invested in increased R&D, worker training and higher compensation; 94% of profits now

Although there are countless examples of nonprofits doing spectacular work, all too many “settle for mediocrity or cause potential harm to those who have given their trust,” as social sector leader Mario Morino has starkly put it.

Twenty-five years ago, Drucker warned that if smaller government was politicians’ driving goal, “it is predictable that the wrong things will…be cut—the things that perform and should be strengthened.” Sure enough, since 2017 the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has been gutted.

One of the great challenges now before us is to see below the daily turbulence into the deep currents that have brought us here. “Defining the problem may be the most important element in making effective decisions,” Drucker wrote, “and the one managers pay the least attention to. They try to cure the symptom rather than the disease.”

The problem as the Drucker Institute sees it is not that business is inordinately focused on short-term financial gains, that too many nonprofits are ineffective or that government is both too big and too small. These are all symptoms.

The disease is an abdication of responsibility. “If the managers of our major institutions . . . do not take responsibility for the common good,” Drucker reminded us, “no one else can or will.”

This publication shows how the Drucker Institute is contributing to a cure.

What is heartening at such a difficult time is that large numbers of managers and organizations from all sectors are reclaiming responsibility for the common good and countering the negative trends with positive ones: Stakeholder capitalism. Lifelong learning. Reinventing government. Social innovation.

Peter Drucker, whose writing and thinking can be found at the root of each of these movements, would have identified them as advancements “already trying to happen on their own.” Our strategy at the Drucker Institute is to lean into the things trying to happen, to leverage the momentum of these movements, to use their burgeoning reach and power to amplify and extend our own work.

That doesn’t mean our aims are easily achievable. In many cases, powerful forces are lined up to resist change and, even where they’re not, inertia alone can make the status quo seem unshakable.

But shakeable it is, and the Drucker Institute has had a greater impact than any of us would have dared hope when it was founded 13 years ago. Day by day, working hard, we’re chipping away at what ails society. In the pages that follow, we hope to give a sense of how we’re part of the remedy.

— Zach First, Executive Director

Lifelong Learning

Lifelong Learning

Lifelong Learning

Lifelong Learning

A decade ago, lifelong learning was an ideal. Today, it is an imperative.

The McKinsey Global Institute estimates that up to 800 million global workers could find themselves replaced by automation in the next 10 years, and almost nine out of 10 managers surveyed say they face current or imminent skill gaps within their organizations.

“More than a century has passed since the universal high-school movement took off in the United States and 50 years since the college-for-all movement began,” Arizona State University’s Jeffrey Selingo has written. “Now it’s clear a third wave in the evolution of education is needed to compete in a new economy in which learning can never end.”

The Drucker Institute has added to this latest wave through several programs, including our Harbor Freight Leadership Lab, which aims to improve the effectiveness of skilled trades education leaders in public schools across America.

But the heart of our contribution to lifelong learning has been Bendable, a community-based system that allows residents of all ages and backgrounds to easily acquire new knowledge and skills through online courses as well as in-person learning opportunities.

In June, Bendable debuted in South Bend, Indiana, promising to forge a “city of lifelong learning,” while making the community more resilient in the face of a fast-changing economy. Our plan is to expand to more cities in 2021.

It is an initiative that Peter Drucker would have surely applauded. He began writing about society’s transition from an industrial age to a knowledge age more than 60 years ago. But he cautioned that it wouldn’t be easy “to build continuous learning into the job and into the organization.”

“Lifelong learning…requires that learning be alluring,” Drucker wrote, “indeed that it become a high satisfaction in itself, if not something the individual craves.”

In South Bend, thousands of residents have come to Bendable in the first few months to access learning resources from 19 local and national content partners. But it’s more than having a great catalog of courses that is motivating them. They are also attracted by a strong sense of trust, which was nurtured over a long period by the Drucker Institute team getting to know the people and organizations of South Bend; listening to them to understand exactly what they need to learn and want to learn and how they like to learn; and designing the system with them in close collaboration.

It is a tack that makes us different. Many players in the space are attempting to produce digital platforms that can link job seekers with credential-bearing educational providers and then line them up in a new career—all of it at the click of a button or two.

Bendable, by contrast, isn’t powered by an algorithm; it is powered by community.

Stakeholder Capitalism

Stakeholder Capitalism

Stakeholder Capitalism

Stakeholder Capitalism

Before people felt compelled to use the term “stakeholder capitalism” (or “conscious capitalism” or “inclusive capitalism” or “citizen’s capitalism,” as it is variously called) they simply spoke of “capitalism.”

During the 1950s and ’60s, it was widely held that a corporation had a responsibility to deliver value to everyone it touched. “The job of management,” Standard Oil Chairman Frank Abrams declared, “is to maintain an equitable and working balance among the claims of the various directly affected interest groups—stockholders, employees, customers and the public at large.”

But in the 1970s, dissenters began to make a very different case: The interests of those who own a company’s stock should always come first. Within a decade, this was the new consensus. And it has pretty much been that way since then. “We work for our shareholders,” American Airlines CEO Doug Parker said last year. “Our job is to make sure that we’re maximizing value for them.”

And yet, over the past five to 10 years, shareholder primacy has faced a growing backlash among scholars, policymakers and certain business leaders who see that this position has led companies to focus inordinately on short-term profits.

In turn, they say, the obsession with quarterly earnings and daily share price has contributed to exploding income inequality and

environmental degradation, and it has even undermined corporations’ own ability to innovate.

The Drucker Institute has been among those helping to make this case. Through our company rankings and a related financial index, we have used the rigor of good data science to show the tremendous value that is generated when management can effectively serve their shareholders, yes, but also their employees, customers and the greater community.

As Peter Drucker wrote in 1988, far too much in society “depends on the economic fortunes of large enterprises to subordinate them completely to the interests of any one group, including shareholders.”

We still have a long way to go until stakeholder capitalism becomes just “capitalism” again. But we’re getting closer all the time.

Reinventing

Government

ReinventingGovernment

Reinventing

Government

ReinventingGovernment

Just because a movement has been around for a while doesn’t mean that it has grown old. Such is the case with “Reinventing Government,” which was made famous by a highly influential 1992 book of that name by veteran city manager Ted Gaebler and journalist David Osborne. The following year, Vice President Al Gore spearheaded an effort to reform the way the government operates. It included “reinvention teams” and “reinvention laboratories” within different federal agencies.

Peter Drucker’s fingerprints were all over this. Gaebler and Osborne called Drucker “perhaps the single most influential thinker” in shaping their views. And in 1994, Drucker addressed federal officials in Washington as part of the vice president’s initiative, imploring those in attendance to continue focusing on achieving high performance and better serving the public—not just slashing costs; to instill the discipline of continuous improvement; and to set benchmarks, measure results and hold officials accountable for meeting them.

“What you have accomplished is remarkable and important,” Drucker told his audience. “It is the first step. It is time to start work on the next ones.”

In the decades since then, many government leaders have done just that. Although the term “Reinventing Government” is used less frequently these days than it once was, its tenets remain integral to a number of programs dedicated to lifting the performance of public sector officials.

Among them is our own Drucker Playbook for the Public Sector. It trains government employees by sharing Peter Drucker’s most indispensable insights on management and leadership and provides them with tools for effectiveness. Since 2016, when it was launched, the Drucker Playbook has been used by 17 cities across the United States, as well as by the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the Reserve Bank of India.

One organization that has used the Playbook is the fire department in Memphis, Tennessee. Recently, the department’s point person on the project,

Ronny Beasley, took a new job: to be chief of the fire department in La Vergne, just outside Nashville. It’s a transition that Beasley believes owes a lot to the Drucker Playbook, which opened his eyes to new possibilities and to his own inner strengths.

Two months into the new job, which he describes as drinking from a “five-inch hose” (firefighters are precise about this sort of thing), Beasley sat down for an interview to talk about his experiences with the Playbook.

Ronny Beasley

Chief of the Fire-Rescue Department, La Vergne, Tennessee

How did you get into this line of work?

I’m a second-generation firefighter. That’s the only thing I ever wanted to be, except for relief pitcher for the New York Yankees.

How did you learn of the Drucker Playbook for the Public Sector?

I was the chief of training for the Memphis Fire Department and working closely with the Memphis human resources department. The director of that department had set up a session with Lawrence Greenspun of the Drucker Institute.

What did you think?

I immediately saw the value in it. I asked 60 mid-level and senior leaders from the Memphis Fire Department to come to the first session, which was mandatory, and about 25 participants chose to continue and complete all the modules over the next six months.

What was helpful about those sessions?

For me, the Drucker Playbook gave me a tremendous understanding of management and leadership and how they fit together. You know, quality leaders can be managers, and quality managers can be leaders.

What would you say is the difference between leadership and management?

Management is dealing with processes, teams, projects—something that has an expiration date on it. Leadership is about people. It’s how you carry yourself, your facial expressions, your understanding of people, how you sense the pushback or acceptance of what you’re trying to make happen.

Was the Playbook for the fire department customized?

Yes. As we worked, I talked with Lawrence on multiple phone calls about how to bring the content even closer to home for people. So we shared what we had

in meetings, and Lawrence built a very solid playbook.

The Drucker Playbook focuses a lot on departmental missions. How did that work for the Memphis Fire Department?

While we already had mission, vision and goals set out by our fire director, we did not have those things defined for each division of the department: logistics, training, apparatus maintenance, fire suppression, EMS, public education on fire prevention—all of these needed to set out their missions.

What was challenging about introducing the Playbook to a fire department?

If you’re asking someone to change their ideas or their processes, they’re giving up something. You have to be understanding of that loss. Because of the fire service’s traditions, we’ve done things one way for 150 years.

What helped people to come around to the Playbook?

We made sure to have people from all divisions and levels in on the process and in the same room. When you hear someone from the alarm office or dispatch office explain to others how their process works and how they’re trying to meet our needs and the needs of the citizens of Memphis, the global picture begins to grow. For the first time in a very long time, the Memphis Fire Department was explaining our processes to mid-level people and those with boots on the ground so they could see how and why we set our mission, vision and goals.

You’ve said that the Playbook also played a role in getting you your current job. How?The Playbook gave me a deeper understanding of management and leadership, instead of buzzwords. And through these projects I was working on and these training sessions I was doing, I started to realize: Hey, I’m more capable of this stuff than I knew.

What’s an especially formative experience you can share with up-and-coming firefighters and leaders elsewhere?The first happened on the day after Christmas in 1992, when I’d been out of class for just two months and our rookie company was dispatched to a fire in a church that had collapsed. There were two firefighters trapped inside, and the battalion chief there was under terrible stress, which I could hear in his voice and see in his face. He grabbed my lieutenant by the collar and yelled and took off and ran toward the structure. I was going to chase after the battalion chief because he was the boss, but my lieutenant grabbed me and said, “We don’t run. We walk. We move fast.” Later, he told me why. If you run and you’re out of breath, you don’t get to size up the situation, and you won’t get a good outcome. My lieutenant was very strong and confident, very calm, and I saw a model of leadership that day.

“The Playbook gave me a deeper understanding of management and leadership, instead of buzzwords… I started to realize: Hey, I’m more capable of this stuff than I knew.”— Ronny Beasley, Fire Department Chief, La Vergne

The second experience happened 11 years later, and that day I had to tell a young firefighter the same thing my lieutenant had told me, under similar circumstances. There was a commercial structure on fire, and two firefighters were trapped inside. Looking at the fire loads, I could see it was a bad situation. A team had already pulled one guy out of the building, someone I knew very well. We were sent to the rear to try to make an attempt to rescue the second firefighter.

When we’d gone roughly 35 or 40 feet into the building, the fire chief called me on the radio. She told me she was pulling us out, which meant leaving a firefighter on the ground. That is a very painful decision. Typically, I’d have said: “Give me a few more minutes, we’re close.” But I recognized in her voice that there was no option. We retreated, and I announced we were out. Nineteen seconds later, the building collapsed, exactly at the place where we’d been when she ordered us out. The decision had saved the lives and changed the lives of four people.

Had I just run in there, I would’ve missed the things I needed to see that day: where the smoke was coming from, where the structural integrity was lost, the color of the smoke. I can still see them now. That’s what allowed me to say: She’s right. We’ve got to leave. So those were two lessons for me in leadership. They were tragic. However, they also made me who I am as a chief officer and, I think, husband and father.

Do you see the Drucker Playbook playing a role in the La Vergne Fire Department?

It will in some capacity, whether they know it or not! I really believe that the Drucker Playbook has had an impact on me as a manager and as a leader. I hope it will have an impact on this organization that I’m working for now. And I know that for the people who participated in Memphis, the Playbook will have an impact on their career, on the people they lead and the community they serve.

Illlustrations by Emilie Hahn

Social

Innovation

Social Innovation

Social

Innovation

Social Innovation

Nobody knows exactly who coined the term “social innovation,” but

it is quite clear who was among the first to discuss its importance in addressing the myriad challenges of the world: Peter Drucker.

“We need social innovation,” Drucker wrote in his 1959 book, Landmarks of Tomorrow, “more than we need technological innovation.”

Today, of course, the concept of social innovation is so widely understood that the Stanford Social Innovation Review is published without people wondering what sorts of articles they’ll find on its pages. The Social Innovation Research Center, the Sol Price Center for Social Innovation at the University of Southern California and the Cambridge Centre for Social Innovation do their work without a lot of need for explanation.

In the time between Drucker’s original ruminations and the emergence of today’s social innovation movement, much has evolved. Originally, the social innovations of which Drucker wrote were all products of government or business: the Marshall Plan, commercial insurance and myriad other breakthroughs. Now, a third arena has come to play a leading role—namely, the social sector.

Drucker was ahead of his time here, as well, concentrating on the need for effective nonprofit management when few others were paying attention. “Nonprofit institutions need innovation as much as businesses or governments,” he wrote. “And we know how to do it.”

To Drucker, a crucial ingredient in fostering innovation—the thing that’s new—is to stop doing those things that have become obsolete.

“To call abandonment an ‘opportunity’ may come as a surprise,” Drucker wrote. “Yet planned, purposeful abandonment of the old and of the unrewarding is a prerequisite to successful pursuit of the new and highly promising. Above all, abandonment is the

key to innovation—both because it frees the necessary resources and because it stimulates the search for the new that will replace the old.”

That is why our long-standing program for nonprofit leaders, the $100,000 Drucker Prize, asked social sector leaders to learn about planned abandonment as a part of the application process.

It is also why we have decided to sunset the Drucker Prize and replace it with something that, we believe, will have an even greater impact.

Next year, we will launch a new program called Spring Cleaning in conjunction with the Metro United Way of Louisville, Kentucky, which serves more than 100 nonprofit organizations. Participants will go through a one-day workshop on planned abandonment. We hope to eventually scale Spring Cleaning to other United Way chapters across the country.

Before we do that, however, we want to pay tribute to the dozens of remarkable organizations whose contributions to social innovation earned them the Drucker Prize. Awarded for each of the past 28 years, it recognized the nonprofit that our judges determined best met Peter Drucker’s definition of innovation: “change that creates a new dimension of performance.”

MISSION

MISSION

Strengthen organizations

to strengthen society.

STRATEGY

Offer frameworks for effectiveness,

grounded in Peter Drucker’s

humanistic values, and equip

organizations to put them into

practice.

WINNING ASPIRATION

Be recognized as an essential part

of movements for positive social

impact.

In the long term, we also aspire to

extend the worldwide reach and

impact of Peter Drucker’s values.

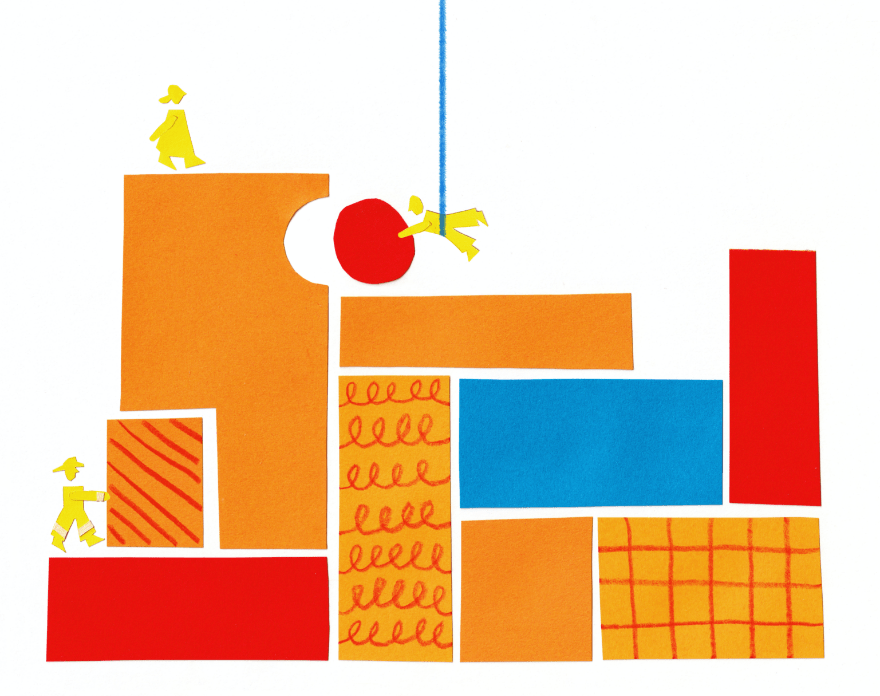

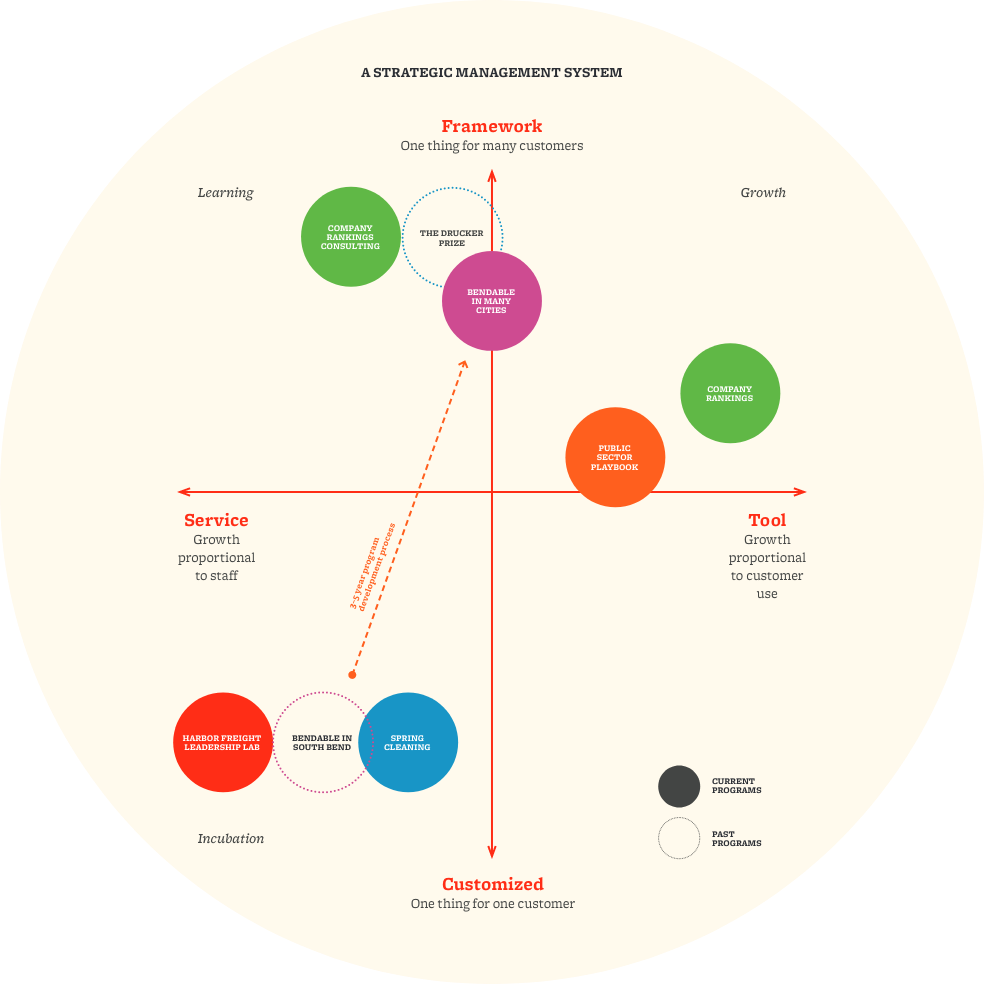

The diagram above depicts how we combine our mission,strategy, where-to-play/how-to-win pairing, and strategic choices into a management system. Each program’s name appears in small caps, e.g., company rankings.

The Drucker Institute develops programs according to the Drucker dictum to “start small [but] aim at leadership.” We begin in the lower left, incubating new programs as direct services designed and delivered for a focused segment of customers. This ensures that our programs develop in immediate contact with, and response to, real customers and their needs.

Over a 3–5 year span, we test whether programs that succeed in the lower left can continue to produce results while we offer them increasingly as tools and decreasingly as direct service, and while we make them available to more customer segments.

Though our goal is to make each program effective and sustainable in the upper right, each always requires a mechanism in the upper left for organizational learning. In some cases this mechanism is a discrete activity, such as our company rankings consulting. In other cases it is woven into the overall program, such as localization for each Bendable city. Whatever the mechanism, our work in the upper left quadrant keeps us in close contact with the organizations that use our tools, and helps us continue.

The Drucker Institute By the Numbers

(With apologies to Harper’s Index)

LIFELONG LEARNING

Percentage of jobs requiring at least some education or training beyond high school: 67

Percentage of adults in South Bend, Indiana, who have a degree or industry-recognized credential

beyond high school: 40

Number of offerings on Bendable to make progress toward a degree or obtain an

industry-recognized credential: 146

Total number of courses and other learning resources on Bendable: TK

Number of residents in South Bend: 102,026

Number of Bendable flyers distributed to South Bend residents in their monthly water bill and food boxes

in the month after the system launched: 110,000

Number of South Bend companies, government agencies, public school classrooms and nonprofit groups that have integrated Bendable into their programming and activities: TK

Ratio by which adults in the U.S. regularly go to the library compared with the movies: 2 to 1

Cost of a movie ticket at the AMC South Bend 16 theater: $7.49

Cost of Bendable to a learner with a library card: $0

Number of new cities Bendable is aiming to expand into next year: 3

Number of people outside of South Bend who, in the meantime, have visited Bendable: TK

STAKEHOLDER CAPITALISM

Percentage increase in payouts to stockholders as a share of total assets of publicly

traded companies since 1972: 72

Percentage increase in wages as a share of total assets of publicly traded companies since 1972: 47

Years that America’s leading CEOs said that serving shareholders was their primary aim: 22

Years since America’s leading CEOs have revised their stance to say that serving all stakeholders is their aim: 1

Years that the Drucker Institute has focused on combating shareholder primacy and promoting

a stakeholder model: 7

Number of major articles in The Wall Street Journal highlighting the Drucker Institute’s

stakeholder-based company ranking system: 26

Number of times that Amazon founder and CEO Jeff Bezos has tweeted about his company’s

No. 1 overall position in the rankings: 1

Likelihood that an S&P 500 company, as compared with those in the top 100 of the Drucker rankings,

laid off or furloughed workers through the first 3½ months of the COVID-19 pandemic: 2 to 1

The premium you would have made, as of TK, had you invested $1,000 in the \S&P/Drucker Institute Corporate Effectiveness Index instead of the S&P 500

Number of copies of Peter Drucker’s The Effective Executive you could have purchased with the extra dough: TK

REINVENTING GOVERNMENT

Percentage of mayors and city managers who discussed leadership in speeches delivered between January and April 2019: 14

Percentage who discussed bridges and tunnels: 14

Percentage of city leaders who say that their municipality excels at using performance

metrics to evaluate and inform decisions: 17

Percentage of Drucker Playbook for the Public Sector participants who learn the importance of effectively using performance metrics to evaluate and inform decisions: 100

Miles between the most spread out users of the Drucker Playbook in the United States—the U.S. Department of Agriculture in Washington, D.C., and the city of Sequim, Washington: 2,863

Total number of “rising leaders” who have been through Drucker Playbook training: 700

Percentage of Drucker Playbook survey respondents indicating that the lessons learned will, over time, make them more effective leaders: 90

SOCIAL INNOVATION

Percentage of nonprofit leaders who say that innovation is an urgent imperative: 80

Percentage of these leaders who say their organization is set up to meet the imperative: 40

Chapter of Managing the Nonprofit Organization in which Peter Drucker introduces the need for “organized abandonment,”

which he calls essential for the sake of “innovation, constant renewal”: 1

Chapter of Managing the Nonprofit Organization in which Peter Drucker again stresses the need for organized abandonment: 2

Chapter of Managing the Nonprofit Organization in which Peter Drucker for a third time stresses the need for organized abandonment: 5

Year that the nonprofit organizations that are part of Metro United Way in Louisville, Kentucky, will have a chance to spur innovation and constant renewal by taking part in the debut of the Drucker Institute’s Spring Cleaning program of organized abandonment: 2021

Number of people served each year by these United Way organizations: 1,000,000

THE WHOLE SHEBANG

Members of the Drucker Institute team making all of the above happen: 13

Add Link dddd

Add Link dddd