“Performing, responsible management is the alternative to tyranny and our only protection against it.”

—Peter Drucker

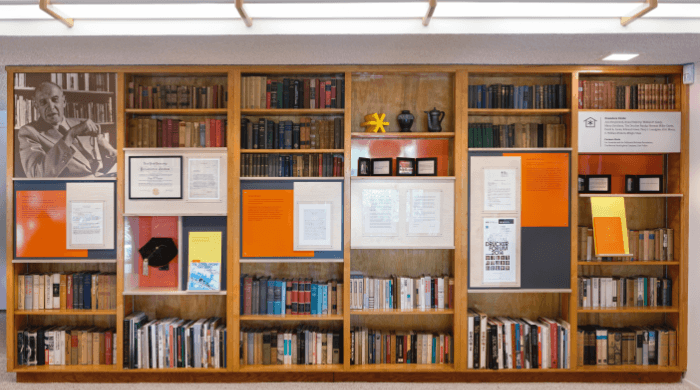

Shortly before he died in 2005, Peter Drucker was celebrated by BusinessWeek magazine as “the man who invented management.” Naturally, when most people hear that description, they think of corporate management. And Drucker did, in fact, advise a host of giant companies (along with nonprofits and government agencies). But he came to his life’s work not because he was interested in business per se. What drove him was trying to create what he termed “a functioning society.”

Drucker had, after all, seen firsthand what happens when society stops functioning. This was the central theme of the first of the 39 major books that he would publish over the course of his extraordinarily long and productive career. The End of Economic Man traced the rise of the Nazis in the aftermath of the Great War and Depression.

“These catastrophes broke through the everyday routine which makes men accept existing forms, institutions and tenets as unalterable laws,” Drucker wrote. “They suddenly exposed the vacuum behind the façade of society.” Looking for a miracle, he added, the masses turned toward the “abracadabra of fascism.”

Drucker was determined never to let things break down like that again. And the only way to do that was to build effective and responsible institutions, including those that by the 1940s were emerging to be the most powerful in the world: big American corporations. Management, practiced well, was Drucker’s bulwark against evil.

Timeline

Drucker as Consultant

In many cases, they were deceptively simple: Who is your customer? What have you stopped doing lately (so as to free up resources for the new and innovative)? What business are you in? For those who worked hard enough to puzzle out the answers, the experience could be truly profound. “If you weren’t already in this business,” Drucker asked Jack Welch when Welch became the CEO of General Electric, “would you enter it today? And if the answer is no, what are you going to do about it?” This led Welch to his pivotal strategy of fixing, selling or closing every business in which GE was not No. 1 or No. 2 in the market. Above all, Drucker pushed his clients to stop simply making plans and to start taking action. “Drucker purified my mind,” said Donald Keough, the former president of Coca-Cola. “He would tell me after each session, ‘Don’t tell me you had a wonderful meeting with me. Tell me what you are going to do on Monday that’s different.’”

Drucker’s imprint was broad, affecting companies across the world.

For instance, “Toyota operates exactly the way Drucker-san said a company ought to operate,” Atsuo Ueda, an expert in the automaker’s vaunted production system, has noted. But Drucker’s imprint was also deep, as Jim Collins observed when he and Jerry Porras were researching their book Built to Last: “The more we dug into the formative stages and inflection points of companies like General Electric, Johnson & Johnson, Procter & Gamble, Hewlett-Packard, Merck and Motorola, the more we saw Drucker’s intellectual fingerprints.” The difference: Unlike so many consultants, Drucker wrote and thought “with such exquisite clarity,” said Intel co-founder Andy Grove. That alone made him “a standout among a bunch of muddled fad mongers.”

Drucker as Teacher

He indulged a lot—lecturing on economics at Sarah Lawrence College beginning in 1939, teaching philosophy and politics at Bennington College from 1942 to 1949, serving as a management professor at New York University from 1949 to 1971, and holding the Marie Rankin Clarke Professorship of Social Science and Management at Claremont Graduate University from 1971 to 2002. Drucker gave his last lecture at CGU in spring 2005, not long before his death, at the age of 95.

Drucker as Writer

Sometimes, if he wanted to be provocative, he’d say that he was a “social ecologist,” observing our man-made environment the way a natural ecologist examines the biological world. Most of the time, though, he’d keep it simple: “I’m a writer.”

INTERVIEWER: If you describe your occupation, would it be ‘writer’?

DRUCKER: I always say I write.

INTERVIEWER: What, then, has inspired your books more than anything?

DRUCKER: The same thing that inspires tuberculosis. This is a serious, degenerative, compulsive disorder and addiction.

INTERVIEWER: An addiction to writing?

DRUCKER: To writing, yes.

Through some 10,000 book pages and countless articles, Drucker displayed incredible powers of observation—to “look out the window and see what’s visible but not yet seen,” as he put it. In fact, he discerned many of the major trends of the 20th century before almost anyone else did: the Hitler-Stalin pact, Japan’s impending rise to economic power, the shift from manufacturing to knowledge work, the increasing importance of the social sector, the fall of the Soviet Union. Above all, he wrote about the need for all of our institutions to flourish in order to have a functioning society. In this way, “probably no writer of the second half of the 20th century has had more influence for the good,” Jack Beatty, Drucker’s biographer, has asserted. Drucker wrote 39 books in all. They were mostly about management, economy, polity and society, but there were two novels among them.

Drucker and the

Social Sector

As the story goes, the concept was so counterintuitive that many readers thought the magazine had made a huge typo; surely, it had gotten things backwards. Anyone who was familiar with Drucker, however, knew that he believed in the power of the best nonprofits not only to be effective and highly impactful for the recipients of their services, but also to provide a much-needed sense of fulfillment for their volunteers. “Citizenship in and through the social sector is not a panacea for the ills of … society,” Drucker wrote, but it “restores the civic responsibility that is the mark of community.” Drucker advised the American Red Cross, the Salvation Army, the American Heart Association, the Girl Scouts of America and many others. In 1991, he created the Peter F. Drucker Award for Nonprofit Innovation, which remains among the Drucker Institute’s core programs.

Drucker as Guru

That was surely overstating things. But there is no doubt that they admired him. Tom Peters, the co-author of In Search of Excellence, called Drucker “the creator and inventor of modern management.” Harvard’s Rosabeth Moss Kanter once remarked that “Peter Drucker’s eyeglasses must contain crystal balls because he anticipated so many trends.” Michael Hammer, whose Reengineering the Corporation was the best-selling business book of the 1990s, commented: “I have had the privilege of sharing a podium with Peter Drucker; on such occasions, I felt as though I was playing back-up horn for the archangel Gabriel.” As for Drucker, he actually hated being called a “guru.” People used the word, he said, only because “charlatan” was too hard to spell.